Dad’s energy spiked that last winter, just in time for opera season. Nothing compares to the Met in New York, of course, but the Los Angeles Opera at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with Placido Domingo as director was very good that year.

We bought a series of six operas in an orchestra section where Dad would be comfortable in his wheelchair. We had early dinner at a little bistro down the street and settled in for a performance of Tosca.

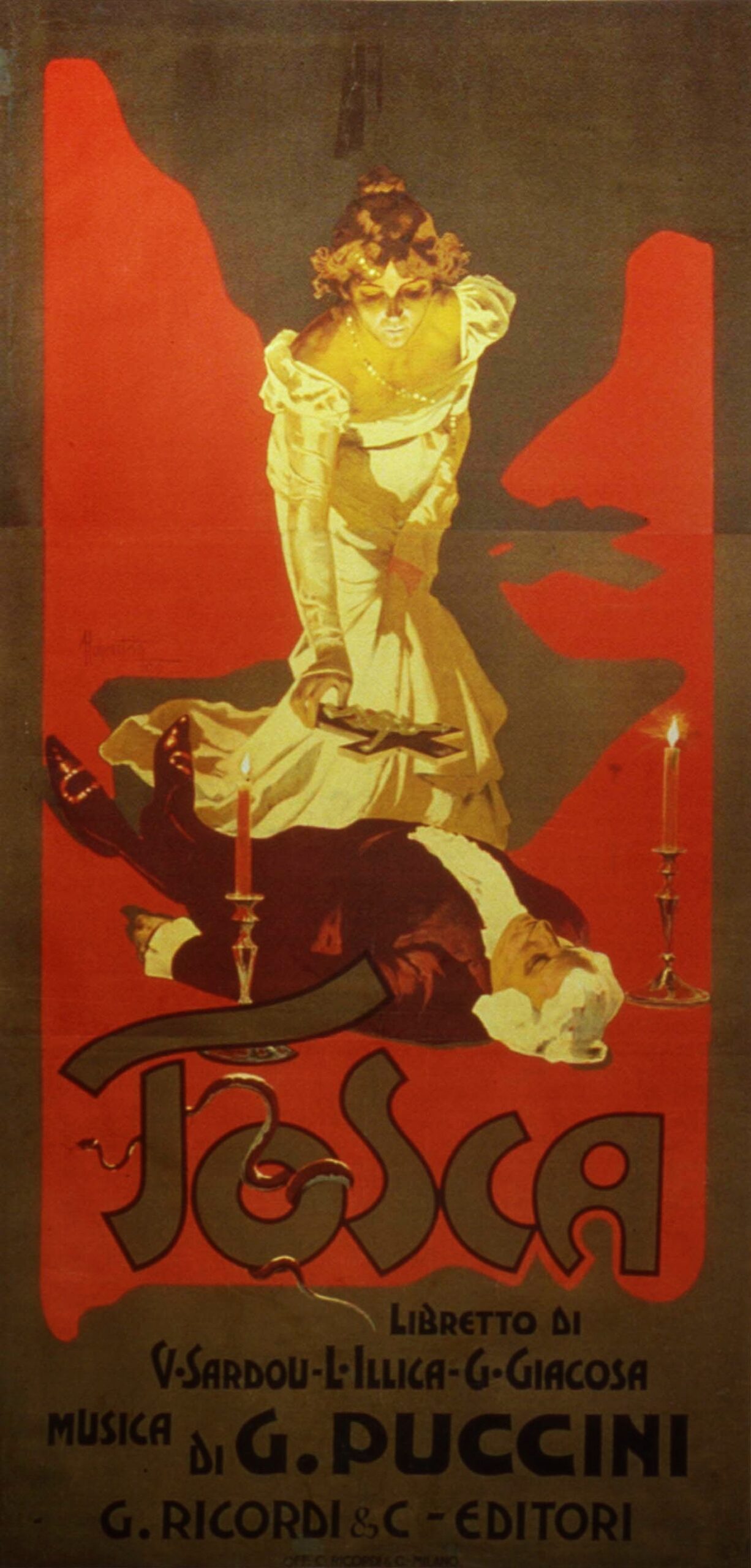

Tosca, my favorite opera, is a heartbreak of a story, and (usually) the artist who plays her is as large physically as vocally. This Tosca was massive, with a voice to match.

The opera ran long. We were on our way home in our Mercedes sedan when the warning bells sounded on Dad’s oxygen compressor. Try as I might to diagnose the problem while I was driving, the alarm suddenly changed to signal we had just minutes of oxygen left. We were close to the Manhattan Beach exit on the 405 freeway, so I put on my hazard lights and took off. Dad was slumped in the passenger seat, but was conscious. “Easy breaths, Dad. I’ll have you on electric in just a few minutes.”

An L.A. police cruiser follows me off the exit, lights going and sirens blaring. I know these roads well, so I get around other cars easily and speed toward the beach. A black Manhattan Beach SUV cruiser joins the chase. I am running lights and speeding as carefully as possible. We’re going to dead-end at the water, so they can’t be very worried we are trying to get away.

The last few blocks are a maze of small back streets, which I take tight and fast. Dad has been off oxygen for ten minutes. I’m fifty yards from our garage when I hit the opener on the visor and the house lights go on. I skid into the garage and engage the door. I scramble to the back seat and roll out the door as the cops start pounding on the garage.

I have industrial cables on a cart Dad used when he was better. I pull the cables, plug the compressor in, and wait for the lights. The cops must be using their billy clubs, I surmise, because the banging is getting louder. I’m just waiting for one of them to go around front and break down the door.

The green lights on the compressor fire up and the machine begins to rumble. Dad has managed to open his door and throw his legs out. His color is bad. I raise the compressor to five liters, its maximum.

“Hang on,” I say to Dad as I walk to the back of the car, open the garage door, and raise my hands high. The doors swing open. Two officers have guns leveled on me and the other two have their hands on their holsters.

“DON’T MOVE.”

“Please don’t shoot officers. I’m a doctor,” I lie. “My father’s oxygen compressor malfunctioned.”

“Why did you close the door?”

“I had to hook the compressor up to the electric in the house. If you stopped me, he’d be dead.”

Everyone holsters their guns. “Do you need a bus, doctor?”

I turn to look at my father. He is breathing deeply. The compressor is pumping for all its worth. Jimmy puts his hand up to signal he’s OK.

“I don’t like his color, but he’s getting five liters now. He should be fine. I’m really sorry, fellas. I had no other choice. We barely made it.”

“Just let us know if you need a bus. We’ll wait.”

I go to Dad and eyeball a vein in his neck, like I was taught. It looks strong.

“We’re going to be OK, officers.”

They go to get back in their cars. I give them thumbs up.

“The opera was good tonight,” I say.

“It was great. You see the size of that Tosca?”

“Yeah, she was big all right.”

I engage the door and seal us up good and tight.

“You want a nightcap?”

“You read my mind, son. Hey, imagine if I didn’t make it tonight. You could tell everyone I was killed by the fattest woman on Earth.”