I returned to Rome in January 1986, following Paul Castellano’s murder in New York, still smarting from the image that my father might have been killed in front of Spark’s Steakhouse on the night of December 16. Knowing him as I do, I am quite sure his last thought would have been, “I wonder what the specials are tonight?”

Leave it to a bunch of crude fucking wops with big hair to forget that killing a man is horrible; killing him before he knows the specials of the night is unspeakable. Dad described Paul’s private funeral as sorrowful. As usual, he did not hide out in the Hamptons, but kept his firm churning in his glass office high above Madison Avenue.

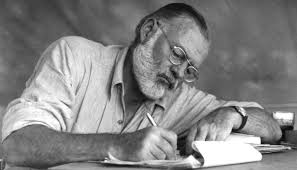

I settled back in to my studio in the Trastevere section of Rome, writing for the International Courier. As luck would have it, while I was in New York, Ernest Hemingway’s last posthumous work, The Garden of Eden, was being readied for publication. At that time, Hemingway had been dead for 25 years, so this book made quite a sensation in the U.S. My editor blocked out a spread in the center of the newspaper and gave me a deadline of one week to fill the pages.

Few could argue that Hemingway’s simple, masterful narration was a wonder to behold. Until the assignment in Rome, Hemingway was never a favorite writer of mine. I viewed many of his themes as “forced” — as if to teach boys what it is like to be a real man. It didn’t help that my college friends — boys on their way to manhood — all idolized Hemingway. So, I did what I always do. Since women in college overwhelmingly preferred Fitzgerald to Hemingway — I went over to the winning side, and thumbed my nose at the boar hunter.

With the back-to-back publications of The Sun Also Rises, Men Without Women, and A Farewell to Arms in the course of four short years (1926-1929), Hemingway became the first literary ‘rock star’ of his generation. He was often pictured at the most elegant parties in Paris, or fighting giant fish off the coast of Cuba. His wives were beautiful, his friends were urbane, and a red carpet seemed to appear under his feet wherever he roamed.

But it was the publication of his shortest novel that brought Hemingway both his greatest professional accolades and prefaced his deepest sorrow and tragedy. The Old Man and the Sea won the Pulitzer Prize in 1953. The book was specifically cited in 1954, when Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Ernest Hemingway committed suicide in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

From the time he won the Nobel to his death was shorter than a decent bottle of California Cabernet Sauvignon ages in its cask. I didn’t know at the time that I was a budding psychopharmacologist, so I tried to avoid Hemingway’s depression and suicide and let the books speak for themselves.

Try as I might, I could not shake the lone image of the author’s last hours in the cabin. It was not maudlin curiosity that pulled me in that direction, but I somehow reasoned that The Old Man and the Sea and Hemingway’s suicide were somehow inextricably linked. I couldn’t prove that, of course — there was no web to fall back on in 1986 — so I would follow the clues Hemingway left for me in his books. I crossed my fingers and settled in for a long read.

During the five years with my father, when death was often at our door, I pulled The Old Man and the Sea from a shelf with great regularity. The more time I spent with my 93-page hard cover Scribner Edition, the more it spoke to me. What it said was keep your back strong and level the bow. Know your bearings in relation to the horizon so you don’t lose your way. And keep your knife sharp and handy to fight what comes as hard as you can. Because sooner or later, the blood will seep into the water and they will come. So make ready.

I realized, then, toward the end of Hemingway’s life, that he had just “let go” of any preconceived notions of manhood, and that this state of mind had transformed his writing. The Old Man and the Sea shows something Hemingway kept buried deep inside: His sense of fatalism — the inevitability that some things are predetermined and cannot be altered no matter how much force we apply. He wove this sense of fatalism deep into this simple novel — during a time when the Black Dog was at his door — and created one the most unforgettable literary masterpieces of the 20th Century.

Hemingway’s description of the Old Man matches in great detail that of my father as he neared the end. The brown blotches that the “sun brings from its reflection on the sea were on his cheeks.” Deep wrinkles creased the back of his neck and “ran well down the sides of his face.” These scars were “as old as erosions in a fishless desert.” Everything about him was old, except his eyes, which were “cheerful and undefeated.”

The themes of The Old Man and the Sea were just as significant and steep. An old man fishing alone in a skiff out of Cabanas, hooked a great Marlin on a heavy handline, pulling the skiff miles out to sea. The old man stayed with the giant marlin a day, a night, a day and another night, while the fish swam deep and pulled the boat. Finally, the old man was able to lash the giant fish alongside the skiff. As the Marlin’s scent leached into the ocean, the old man suffered greatly as he fought off sharks all night, stabbing at them with a club and then an oar, until he was exhausted and the sharks had eaten all that they could eat.

Days later, when the Old Man, Santiago, finally returns to the harbor, bloodied and exhausted, everyone is asleep. In the morning, fisherman and tourists crowd around the skiff to look at the skeleton of the great fish lashed beside it. The Boy, Manolin, who had been waiting and watching for the Old Man for days, snuck into his shack to see that he was breathing.

As the Old Man drifts in and out of consciousness, he tells The Boy what he can about what had happened at sea before he falls asleep again. Even though the Old Man had lived his life on the sea, he no longer dreamt about the ocean, Hemingway tells us — but only about his childhood in Africa, where he watched lions frolic on the white sand. That early image had invaded his dreams and made him happy.

The last line of the short novel is vintage Hemingway and tells us everything there is left to tell. As The Boy sat by his side, crying and watching him, fearful that he would die, “The old man was dreaming about the lions” of his childhood.

I watched my father sleep the Saturday night before he died, unaware of what the morning would bring as I finally climbed into my own bed…