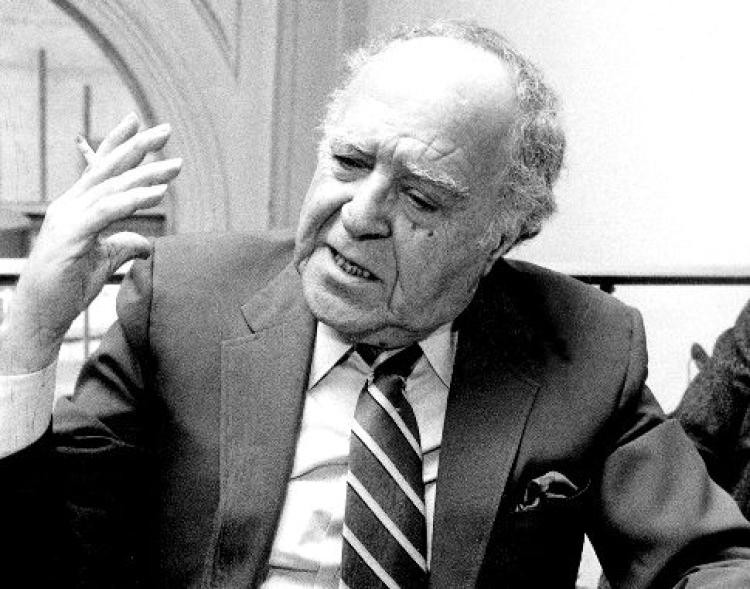

By the later part of the 1970s, my father was already a household name in legal circles, had won awards from esteemed groups, was declared one of the “100 Smartest New Yorkers” by a National Magazine, lived in a 12-room Park Avenue floor-through, owned a French Tudor home in Greenwich, CT, and was as close as a son to the streetwise Democratic Leader of New York, Meade Esposito. In fact, he was Meade’s lawyer. It seemed as if he was everyone’s lawyer.

In those days, the Democratic Leader handpicked many of the state judges — a throwback to the Tammany Hall days that would die with Esposito. Meade would often ask Jimmy to sit with him as the candidates for judgeships — hat in hand — went to receive the blessing of the all-powerful political leader.

Dad and Meade used to laugh in between interviews as they drank espressos and Sambuca. Dad would say, “you know half these guys think that they owe their judgeship to me.” And Meade would tell him that’s exactly what I want them to think. Jimmy walked Meade through so many legal entanglements over the years that billing him was more trouble than it was worth. This was Uncle Meade’s payback.

In the days of $99 flights on Eastern Airlines, our family would fly to Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, just north of Miami, almost every weekend in the winter, and drive 30 minutes west into the Everglades on the proverbial “Alligator Alley,” where one of the first residential homes/golf course/spa was built by a client and friend of Dad’s, Mel Harris. Meade bought the house directly across the street from ours. On New Year’s Eve, after we had eaten dinner, we’d go over to Meade’s where he had bottles of ice cold Dom Pérignon waiting for us and we’d all hail the New Year.

Meade’s wife, Ann, was something of a mystery. She guarded her privacy at all times, even on New Year’s Eve. Meade used to refer to her as “Hugo.” One day Uncle Meade explained: “Every time I said to her ‘we have a dinner to go to,’ she’d reply, ‘you go.’” Thus the nickname, H-U-G-O.

I had never laid eyes on her until one of our New Year’s rituals. I was a young teenager, buzzed on the Dom, looking for a bathroom, when I accidentally entered a room. There was Ann, sitting in a chair, as peaceful as the Old Testament character, Job. She invited me to sit — insisting I call her by her first name — and we talked for fifteen minutes or so. Either she liked me, or was just hungry for human contact. We hugged as I quietly left her bedroom to find the bathroom. Every New Year’s eve thereafter we spent with Uncle Meade, I accidentally got lost on the way to the toilet and had my little celebration with Ann.

One time, as Meade was walking us out, he decided to come to our house for a nightcap. As we were crossing the street, I looked back at the Esposito house and Ann was at the front window. She gave me a wink and a little wave, which I returned with the same. Nothing got past Meade — anywhere, anytime. When I caught up to everybody, he gave me a long sideways glance, as if to say “you’re alright kid.” I was brought up to respect my elders, and that was that.

During two summers in college, Jimmy pulled a few union strings and I sailed as an Ordinary Seaman on merchant vessels to the Middle East, Europe and the Caribbean. I did everything from water-blasting the cavernous oil holds to cleaning heads.

Docking is a tense time on an oil tanker — especially in the Gulf of Mexico — and we were all scrambling on deck when a little prick of an engineer got on my case about doing something wrong as I was signaling one of the tugboats that its spring line was coming loose. I was trying to ignore the prick when two of the biggest Able Bodied Seamen just about pinned the engineer to the deck by his ears. I only found out weeks later that the experienced guys were told to “watch out for the kid” before we sailed.

When we docked finally, I had a moment of rotten luck as the embarrassed engineer and I found ourselves alone in the machinist room. Like the dope he was, he came at me with something big and metal that he could barely throw. I picked a smallish 14-inch wrench off the wall and gave him a light crack on the side of his head. An hour later the third mate came to my bunk to fire me. He liked me — I could hear the regret in his voice. The last words from the two big guys who helped me out on deck were, “Don’t worry, we’ll take care of that fucking engineer.” I set off down the gangway with about five grand in my pocket and all of New Orleans at my feet. I had a blast while that little prick took the beating of his life.

Back in New York two weeks later, I picked up the ringing phone and Uncle Meade was on the line. “What are you doing home so early? You a lazy fuck or what?” I laughed. I knew he knew, so I didn’t even bother to go into what had transpired.

“Tomorrow, you go to the Brooklyn Navy Yard and see my friends, Martini & Rossi.” A guy called in the morning with some spooky instructions about where to meet M & R.

For the rest of the summer and most of the next school year, I worked the midnight shift helping machinists drill parts for Navy carriers and battleships. The bottom line was that when Uncle Meade called, you’d better have your shoes laced up and your jock strap on tight.