”No matter how long you tame a wolf, he will still look to the woods.

Yiddish proverb

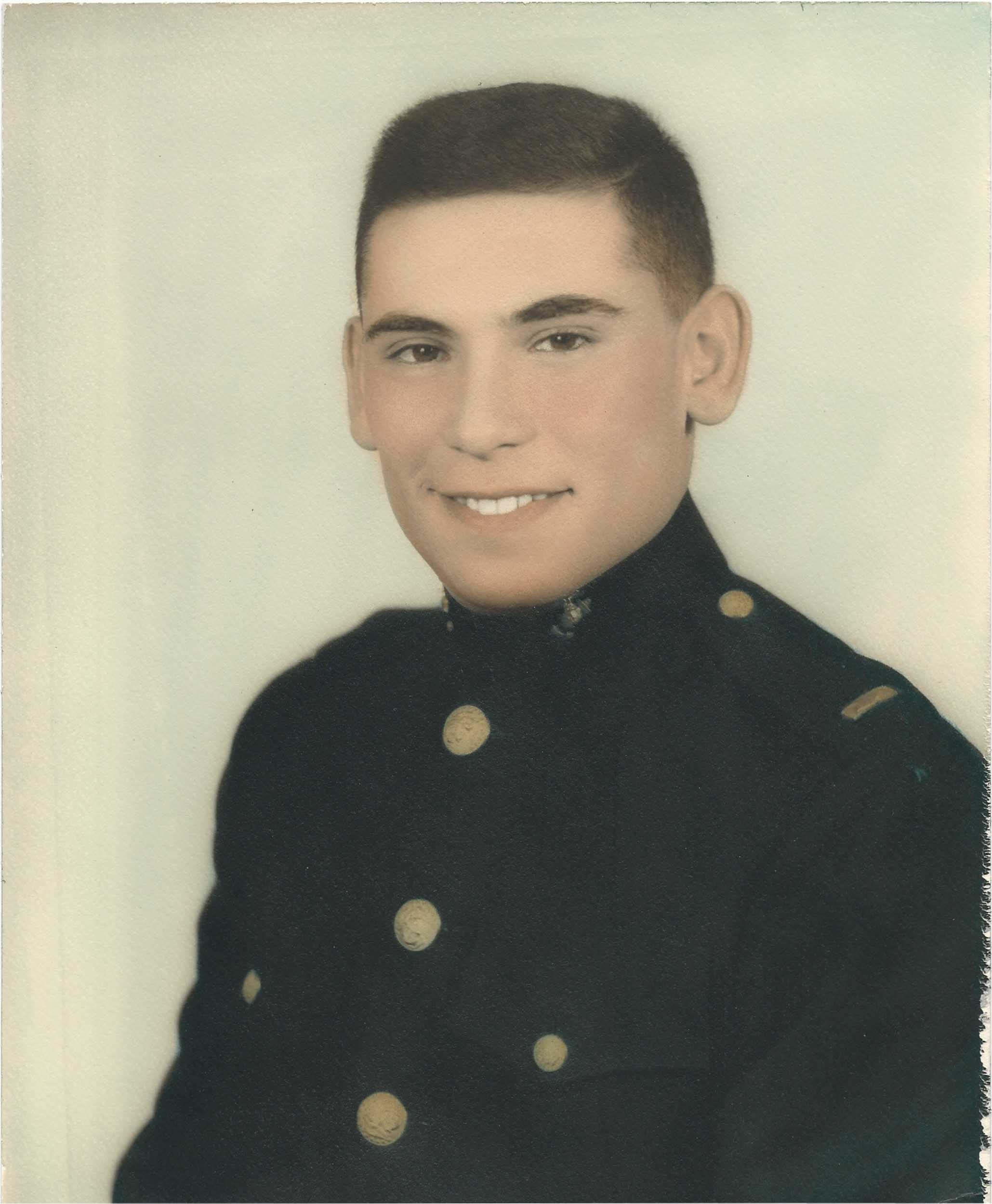

When I look back at Jimmy’s life, I can see the auspiciousness of the era in which he was born. If you really want to know what stars aligned to create this powerhouse of a legal mind with a lightning-fast tongue, look no further than the “accidental” circumstances in which he discovered that lawyering would serve him very, very well.

In 1952, twenty-one-year-old Jimmy La Rossa left New York for the very first time. From that day forward, one can see quite clearly that he was blessed with two critical “gifts.” He had the guts of a prizefighter who had never been knocked down, and the celestial luck of a guy who could land the Space Shuttle on the Hudson River while popping open a bottle of champagne. How he became this way is a mystery. All I can tell you is that it started at Camp Pendleton in Southern California and ended sixty-two years later in Manhattan Beach, California—about eighty miles north of the camp as the crow flies.

Like everyone his age, Dad idolized the men who fought in WWII. Dad and I could watch Band of Brothers and The Pacific for weeks on end. When Jimmy’s number came up for induction into the Korean War, he was a junior at Fordham and wanted to finish. So, instead of letting the Army induct him immediately, Dad walked into a Marine Corp. recruiting office and cut a deal with a young Marine officer. If they gave him one more year of school, he swore he’d go straight to Quantico, Virginia, for training, then to Camp Pendleton for Officer’s Candidate School, and then they could do what they wanted with him. My grandfather, a postman who was retired by fifty-five, was incredulous, as Jimmy had nothing whatsoever in writing. But true to his word, the day after Jimmy graduated from Fordham University, the Marine was at the door.

Jimmy was a week into basic training at Quantico when another Marine, the son of a member of Congress, died of dehydration. Dad’s class was coddled as the Secret Service descended on Quantico. He did, however, have a significant obstacle facing him. He couldn’t shoot.

Jimmy had two big reasons to hate guns. As a second lieutenant leading a training platoon in Japan, an experienced enlisted man tried to help a young private by using his rifle to pull the boy up a steep hill. The carbine went off and the private died in Jimmy’s arms.

At Quantico, Dad failed to qualify with an M-1. The first time he shot it, the sharp metal site was too close to his face, so he got the shiner of a lifetime. From then on, Jimmy was scared of the rifle. He failed the marksman test again and again, putting him way behind his classmates, who were steadily being dispatched to fight in Korea. I have no excuse for not knowing how Dad finally convinced a career Marine Corp. gunnery sergeant that it was in the country’s best interest to let him pass and move on to Camp Pendleton. It seems incomprehensible, but that was Jimmy.

The giant Marine/Navy complex that is Camp Pendleton is about a ninety-minute drive south of Los Angeles. It was a sleepy area in those days. Jimmy started out from Virginia by bus. When he was changing buses in a small southern town, curiosity got the best of him and he went in to a club to hear jazz music. He sipped whiskey at the end of the bar, chatting up the bartender as he was the only white man in the place. “Go get ’em, General,” the barman said as Jimmy left with a skip to his walk. The bus had left, so he killed a day in town until the next bus. He was yet to become the world traveler with a favorite room at the Ritz and a platinum card from flying the Concorde, so he kept getting on the wrong buses, circling the Southwest until he reached the Pacific Ocean and could go no further.

The commanding officer (CO) at Pendleton had little sympathy for the cocky young officer-to-be as he presented his papers in August, 1952.

My father stood at attention in front of the CO. The conversation, and what followed, as Dad described it, went like this:

CO: Let me get this straight. You were dispatched from Quantico six weeks ago to complete your officer’s training here as a second lieutenant in the US Marines while we are at war with fucking KO-rr-EA and you’re just getting here NOW? AND you failed to qualify with an M-1 carbine? But it says here they passed you anyway?

SOLDIER: That’s correct, Captain. I have other skills.

CO: Are you a wise guy (looking at his orders), Second Lieutenant James Michael La Rossa from Brooklyn, New York?

JIMMY: To tell you the truth, I got lost getting here. I stopped here and there.

CO: You stopped? For what, son?

Jimmy gives him a hard stare. He’s getting annoyed.

CO: Well, I hope you had fun because there’s not a bunk left in the camp.

Jimmy turns, picks up his duffel, and heads for the door.

CO: Where you going, Lieutenant?

JIMMY: Back to Quantico to tell them that Commanding Officer Whatever Your Name Is was just full up with lieutenants, which is just as well because he can’t even pronounce the name of our enemy. IT’S KOREA, professor. K-O-R-E-A.

Jimmy turns, salutes, and walks out, slamming the door hard behind him.

Later in the day, the CO leaves his office and heads for his car. He stops and stares in amazement. That same kid from Brooklyn is playing handball against a wall with a bunch of other Marines. He doesn’t have a glove, so his hand is bleeding, but he’s beaten everyone. His pockets bulge with cash. Jimmy sees the CO and walks to him.

CO: I thought you’d be halfway to Virginia by now.

JIMMY: You play, Sir?

CO: I thought I did until I saw you play. I have an extra glove somewhere.

JIMMY: Thanks.

CO: Listen (softening), I grew up around here. If you head south there’s a little town with a nice apartment house right on the water. The Corp. will pay for your quarters. You can train with your platoon here until your orders come through.

JIMMY: Thank you, Captain!

CO: The town’s called Laguna Beach and the apartment name is The Sunset. Tell ’em Floyd from Pendleton sent you.

JIMMY: (Smiling) “How ’bout a game, Captain Floyd?”

CO: “Don’t press your luck, kid.”

Jimmy snaps to attention and salutes.

Jimmy: “SIR!”

Captain Floyd shakes his head and walks off.

Two months later, Jimmy is out looking at the beach in his boxer shorts, a hot coffee mug in his hand. He lights a cigarette with a lighter that looks like a pistol. (Before Dad adopted his trademark gold Cartier lighter, he collected a series of pistol and rifle lighters, which were always kicking around the house. I guess it was his way of making fun of guns.)

Jimmy walks back toward the apartment and yells, “SURF’S UP.” His entire platoon has all moved to the apartment house. “Morning, Lieutenant,” they greet Jimmy. The men head for the beach with their surfboards.

It’s a slow day, so Jimmy asks one of the men to drop him off at a saloon near base. “Sure, Lieutenant. You are some lucky dude. All the brass around here and the prettiest barmaid in a hundred square miles has her eye on you. Must be that Brooklyn charm.”

Dad would love to talk about the ramshackle bar off a dusty road on the way to camp. A very pretty girl behind the bar slips him a menu. Under the menu is a copy of the New York Daily News she’s been holding for him. He gives her a smile. A bunch of other officers are standing around drinking, eating, and flirting with Jeannie. At the end of the bar is an older, senior officer. Jimmy notices the hat on the bar. He’s a general. The officer plays it cool, putting the hat on the stool next to him. Jimmy nods at the older man.

Jeannie puts a club sandwich in front of Jimmy. She throws him a subtle kiss. The general has an eye on the young lieutenant and sees Jeannie’s air kiss. Jimmy asks softly, “Hey, Jeannie, what’s the guy at the end of the bar drinking? Bring me one and then bring him another. Just tell him it’s on the house, would you, babe?”

She gives him a sly smile.

When the drink is in front of the general, Jimmy continues to read the newspaper, picks up his glass, and takes a long draught. He doesn’t look at the general, but he feels his eyes on him. He lights a cigarette with his pistol lighter.

Dad is reading the paper when a loud sports car skids to a stop in front of the bar. Almost everyone turns to see a new Corvette convertible. An officer in full dress blues comes in and struts to Jeannie.

“Well that’s it, Jean, I’m shipping out,” the officer announced.

“Shipping out? When?”

“Now.”

(“This guy had it bad for her, the dope,” Jimmy told me.)

She hesitates. “Well, you’ll be missed.”

“Here—take this to remember me.” He throws her the car keys and puts his hand over his heart.

“Mind her till I get back, would you, Jeannie?” He’s out the door and gone.

Jeannie looks at Jimmy and throws the keys to him. The general just looks at the lucky kid and grins. He could use that kind of luck, he thinks! An hour later Jimmy is driving down a dusty road in the Corvette. A sign says “Laguna Beach—1 Mile,” as the serene Pacific appears in the distance. (You just can’t make this stuff up.)

A few months later, Jimmy is playing handball with some of his men at the base. The CO and the same general from the bar are arguing and can be heard through the open window of the captain’s office. They are both motioning to the Marines playing handball.

Finally, the CO stands, salutes, and reluctantly capitulates to the general’s request. The general steps outside. He and Jimmy exchange knowing glances. When the general is gone, the CO stomps out to the handball court. “Lieutenant,” he yells at Jimmy.

CO: I just can’t believe …

JIMMY: What’s wrong, Captain?

CO: Wrong? I shipped 750 men to the DMZ in Korea this week.

JIMMY: So our orders have come through?

CO: OH YES, and I don’t know how you did this.

Jimmy glances at the men and gives them a smirk. He snaps to attention.

JIMMY: Our orders, Sir!

CO: You and your squad have been deployed.

He hands Jimmy the paperwork and stomps off.

“KOREA?” one of the men asks.

“No,” says Jimmy smiling. “Not by a long shot.”

Twenty-five years later, Dad was in a helicopter landing in the parking lot of Giants Stadium with Perry Duryea, a very prominent client who was running for governor of New York at the time. Dad gets out of the copter. As the blades slow, he hears, “Hey, La Rossa—I knew you’d make it.” Sure enough it was the CO from Pendleton. Jimmy grinned. “Fuck you, Floyd,” he responded without a beat and gave him a snappy little salute as he was whisked into the game with Duryea. If you don’t believe that success is the best revenge, try that on for size someday.

By November 1952, Jimmy and his men had settled nicely into life in Okinawa, Japan—avoiding Korea entirely. Jimmy made it a point to treat the older Marines who had fought in WWII with honor, regardless of whether they were officers or not. He would sit and listen to their stories for hours. The vast majority of these men rarely left base—their ingrained hatred of the former enemy still too fresh.

Just before Dad died, Sonya, my English fiancée, who had lived in Tokyo for a short while, gave Dad a copy of a beautiful picture book about Okinawa. Jimmy told us how he used to sneak off to the hot springs for a bath, overlooking the idyllic Bay of Japan. A woman would bring him tea and rub his back with a fragrant towel.

In another stroke of what looked like luck but was preordained, Dad was assigned to be adjutant to the general. One day, the general orders Jimmy to take some confidential papers to HQ in Tokyo. He is to leave on the next Marine transport. Jimmy is the only passenger on a large military plane. There is no door, so he can see down to the empty sea when one of the pilots comes to him and hands him what looks like a parachute.

PILOT: Sorry, Lieutenant, but we’re having problems with one of our engines.

JIMMY: Fix it.

PILOT: Well, if we can’t, you’ll have to jump as you’re carrying secret papers.

JIMMY: What will you guys do?

PILOT: We’ll try to ride the plane down.

JIMMY: That’s exactly what I’ll do. (He throws the parachute back at the pilot.) Go start the engine, jerkoff. If I have to jump out of this plane I’m going to shoot you first!

The plane lands safely in Tokyo. The senior pilot pulls Dad aside to explain that they sometimes play the “bad engine” game so they can have some R & R in Tokyo. Jimmy agrees to meet them in a local bar after he drops the papers at HQ, which he does.

When Jimmy’s cab pulls up to the bar, there are military police (MPs) everywhere and “his pilots” are in handcuffs. Glass and broken furniture from the bar litter the street. That was fast, Jimmy thinks to himself. Nevertheless, these guys are his ride, so this situation has to be remedied.

“Wait right here,” Jimmy says commandingly to the driver, loud enough for the MPs to hear.

“These men are with me,” Jimmy snaps at the senior MP.

“Well, I’m sorry, Lieutenant, but…”

“But they damaged this bar? Is that what you were going to tell me?”

The MP backs away a step.

“Who cares? I am General Tisch’s adjutant. We have confidential papers to return to Okinawa.” Jimmy waves the empty satchel.

He turns to the pilots. “I left you assholes for an hour; you better be able to fly,” he says to the sheepish flyboys.

“Get those cuffs off them.”

“Sorry, Lieutenant, but the bar is …”

“Damages?” Jimmy says, spitting the word at the bar owner. “He wants damages? Here!” Jimmy pulls a wad of Japanese and American currency out of his pocket and gives it to the bar owner, who looks satisfied after counting the bills.

He turns to the pilots. “GET IN THE FUCKING VEHICLE! WE’RE GOING BACK TO THE PLANE. NOW!”

The MPs remove the cuffs as the pilots get into the cab. Jimmy looks at the bar owner with feigned disgust and gives the MPs a snappy salute.

When they are clear of the scene, Jimmy says to the pilots, “That’s the way we do it in Brooklyn, fellas. Now if we go get a drink, can you boys be nice? You’re buying, by the way.”

What happened in Tokyo spread throughout the base like wildfire. The general assigned Jimmy to the JAG Corp. to assist in the defense of Marines accused of crimes. Dad was a natural.

“Dear Mom,” Jimmy wrote his mother in Brooklyn. “Please take the train to Fordham in the Bronx. Go to the dean’s office and give these papers to his secretary. Tell her to please forward the papers to the law school. Enclosed is a recommendation from the chief lawyer of the JAG Corp. and paperwork from Marine General Tisch releasing me from my service early to attend Fordham Law School next September.”

Jimmy bought himself a fancy used sedan with the money he had saved in Japan and headed east—a wholly different man. He was cruising through Texas en route to Brooklyn and the start of Fordham Law School. A fellow Marine—a black staff sergeant a few years older named Earl—is hitchhiking the same way Dad is heading. Like Jimmy, he is still dressed in his Marine fatigues. The only difference between them is that Jimmy has a few more doodads on his shirt and a sidearm—mandatory for all officers.

The Marine is heading home to Georgia, so they ride together for a good long time. Jimmy gets hungry and pulls off the motorway to grab a bite at a local diner. The sergeant declines to go in. Jimmy insists. “Come on—you must be hungry.” Thinking the man is low on funds, Jimmy offers to buy. The sergeant reluctantly goes into the diner with the officer. Jimmy doesn’t notice the sign in the window saying “WHITES ONLY.” Soon there’s a ruckus inside—breaking plates and glass. Jimmy screams, “THIS MAN COULDA DIED PROTECTING YOU SORRY FUCKIN’ ASSWIPES.” We see a chair bust through a glass window. The sergeant runs to the car.

Jimmy is walking backwards, screaming at the rednecks. When he’s almost at the car he remembers he has his pistol. He’s a terrible shot, but he’s madder than he’s ever been. He draws the pistol. One shot discharges in the air and Jimmy jumps. “FUCK,” he yells. He starts shooting at the tires of the cars outside the diner, ducking the sounds of ricochets. Jimmy throws the gun in the car and they race off.

“Well, Earl, we just won’t stop until we find a better class of people.”

“You’re all right, Lieutenant.”

“Call me Jimmy, Earl. The fucking war is over.”

By the time Dad returned to Flatbush, Brooklyn, his greatest fear was realized. He had known his mother wasn’t well, but he wasn’t expecting terminal cancer.

Dad’s only sibling, Dolores, swore that it was his mother who insisted that he not be told about her illness.

His mother meant the world to him. She was the one who pushed him to succeed, while his own father would have been content if he had followed him into the post office—a stable job in any economy. She had taken the subway to Fordham to enroll him in law school. Without his mother, he would never have come to the attention of the Jesuits, who helped him to understand and strengthen his naturally gymnastic mind.

Dad rarely, if ever, spoke about his mother. Her death was just too painful for him. He might have even internalized some blame for her death. But there is little doubt that Jimmy’s mother was his one and only Last of the Gladiators.

His mother neither smoked nor drank, but cancer had spread throughout her entire body. My father described it as a horrible death. He never got over it. Jimmy could not even bring himself to visit her grave. She died just weeks before he started his first-year final exams at law school.

The wealthy scion of the Arnold’s Bakery fortune built our family house in Connecticut. He had built the house with an elevator for his elderly mother. The French Tudor was twelve thousand square feet and had seven acres of fruit trees, a pool, and fields on one of the highest points in the area. When Dad needed alone time, he often fled to one of the nine bathrooms with a good book.

Every now and then I’d see him out walking and smoking among the fruit trees, quietly taking in the enormity of his own success. There was a deep sadness to him at those rare moments. I never disturbed him, but I knew in my bones that he would never forgive God for taking his mother before she could see what he had made of himself.

In the last five years we spent together—when death was often at our door—I never once heard him pray, or address God in any way. His mother was the single unforgiveable heartbreak of his life. It was the grudge of all grudges, and Jimmy took it to his grave.

I pity the fool at the gate.