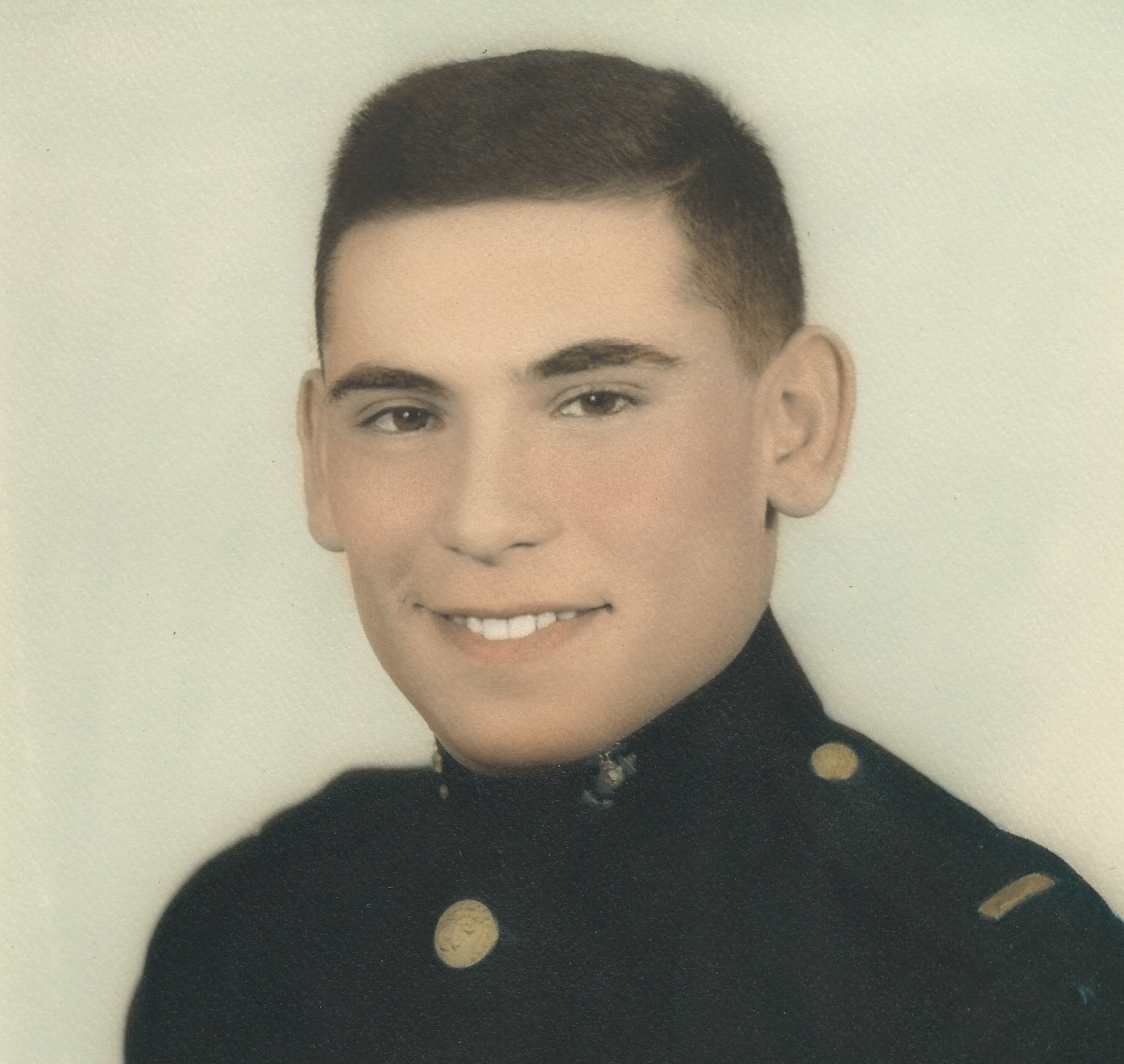

As the Korean War was winding down, my father was finishing up his tour in Okinawa, Japan, as an officer in the Marine Corps. He wrote his mother, asking her to take the subway to the Bronx to enroll him at Law School. He enclosed a recommendation from the chief lawyer of the JAG Corp. and paperwork from General Tisch “releasing me from my service early to attend Fordham Law School next September.”

When he returned to Camp Pendleton, Dad bought himself a fancy used sedan with the money he had saved in Japan and headed east — a wholly different man. He was cruising through Texas en route to Brooklyn and the start of his legal career. A fellow Marine — a black staff Sergeant a few years older named Earl was hitchhiking the same way Dad was heading. Like Jimmy, he was still dressed in his Marine fatigues. The only difference between them was that Jimmy had a few more do-dads on his shirt and a sidearm — mandatory for all officers.

The Marine is heading home to Georgia, so they ride together for a good long time. Jimmy gets hungry and pulls off the motorway to grab a bite at a local diner. The Sergeant declines to go in. Jimmy insists. “Come on — you must be hungry.” Thinking the man is low on funds, Jimmy offers to buy. The Sergeant reluctantly goes in to the dinner with the officer. Jimmy doesn’t notice the sign in the window saying “WHITES ONLY.” We hear a ruckus inside; breaking plates and glass. Jimmy screaming. We see a chair bust through a glass window. The Sergeant runs to the car.

Jimmy is walking backwards, screaming at the rednecks. When he’s almost at the car he remembers he has his pistol. He’s a terrible shot, but he’s madder than he’s ever been. He draws the pistol. One shot discharges in the air and Jimmy jumps. “FUCK,” he yells. He starts shooting at the tires of the cars outside the diner, ducking the sounds of ricochets. Jimmy throws the gun in the car and they race off.

“Well, Earl, we just won’t stop until we find a better class of people.”

“You’re all right, Lieutenant.”

“Call me Jimmy, Earl. The fucking war is over.”

By the time Dad returned to Flatbush, Brooklyn, his greatest fear was realized. He had known his mother wasn’t well, but he wasn’t expecting terminal cancer.

Dad’s only sibling, Dolores, swore that it was his mother who insisted that he not be told about her illness.

His mother meant the world to him. She’s the one that pushed him to succeed, while his own father would have been content if he had followed him into the post office — a stable job in any economy. Without his mother, he would never have come to the attention of the Jesuits, who helped him to understand and strengthen his naturally gymnastic mind.

His mother neither smoked nor drank, but cancer had spread throughout her entire body. My father described it as a horrible death. He never got over it. Jimmy could not even bring himself to visit her grave. She died just weeks before he started his first-year final exams at law school.

Dad rarely, if ever, spoke about his mother. Her death was just too painful for him. He might have even internalized some blame for her death. But there is little doubt that Jimmy’s mother was his one and only Last of the Gladiators.

The wealthy scion of the Arnold’s Bakery fortune built our family house in Connecticut. He had built the house with an elevator for his elderly mother. The French Tudor was 12,000 square feet and had seven acres of fruit trees, a pool and fields on one of the highest points in the area. When Dad needed alone time, he often fled to one of the nine bathrooms with a good book.

Every now and then I’d see him out walking and smoking among the fruit trees, quietly taking in the enormity of his own success. There was a deep sadness to him at those rare moments. I never disturbed him, but I knew in my bones that he would never forgive God for taking his mother before she could see what he had made of himself.

In the last five years we spent together — when death was often at our door — I never once heard him pray, or address God in any way. His mother was the single unforgivable heartbreak of his life. It was the grudge of all grudges, and Jimmy took it to his grave.

I pity the fool at the gate.